Guide to historic map symbols

British broadcaster and anthropologist, Mary-Ann Ochota reveals some of the most common archaeological clues and historic symbols you’ll spot on a map. From church spires to tumulus, this guide will take your though old ordnance survey map symbols.

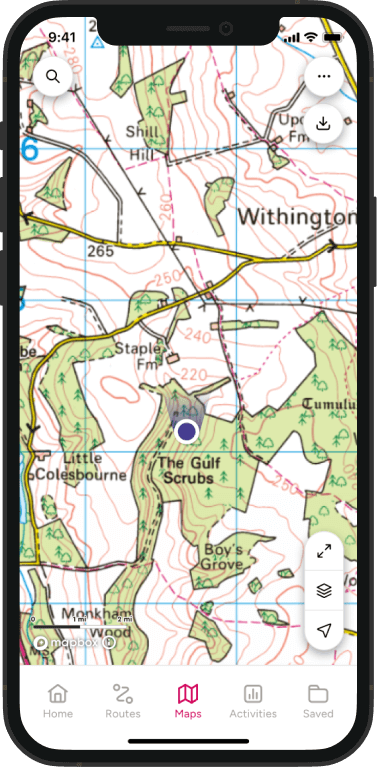

When you look at an Ordnance Survey map – online, on the OS Maps app, or on an OS paper map, there are lots of symbols, each describing different features. Some of these can reveal the hidden history of a place and the more you understand the map symbols, the language of the map, the more it can tell you.

Church symbols on a map

Church symbols are fantastic to navigate by and you can find out a little bit about the type of church, like whether it has a tower or spire, by what’s marked on the map.

This indicates the church has a tower. Saxons usually built wooden churches – if they did build any part in stone, it was the tower. These very old church towers are round. When the Normans arrived in 1066, they rebuilt many churches in stone – their towers are usually made of very thick stone, with tiny windows and rounded doorway arches. Later medieval churches have taller towers, or sometimes levels were built on top of earlier, shorter towers.

This shows the place of worship either has a spire, minaret or dome. In the British countryside, chances are you’re looking for a spire on a Christian church. Spires were constructed from 1200 onwards, in an architectural style known as ‘Gothic’.

This is a place of worship with no tower or spire. These might be chapels or meeting houses, where the architecture is a lot more domestic in style, representing a different style of worship.

Land markings on a map

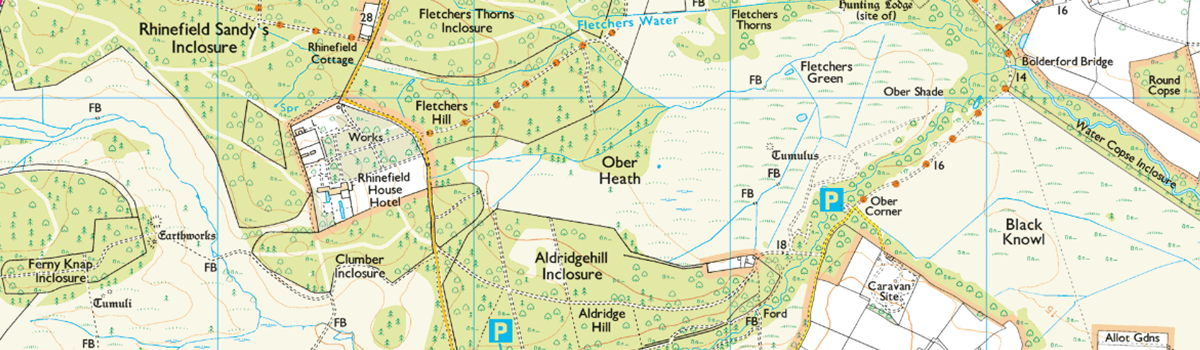

Gothic script on maps

When you see a gothic label on the map, it means the site is definitely archaeological, but one that isn’t Roman. The feature will usually be prehistoric (ie before AD43), or medieval (from the 400s AD until around 1600), or slightly later.

There are lots of examples in the ancient woodlands of the New Forest

Mound – may be an ancient burial mound (also sometimes labelled as ‘Tumulus’ or plural, ‘Tumuli’), it may be a burnt mound of stones that was possibly used in prehistoric times for cooking, or it could be a pillow mound, which is a manmade medieval rabbit warren.

Field systems, settlements and enclosures are often low earthworks that are the final visible remains of houses, fields, tracks and land boundaries.

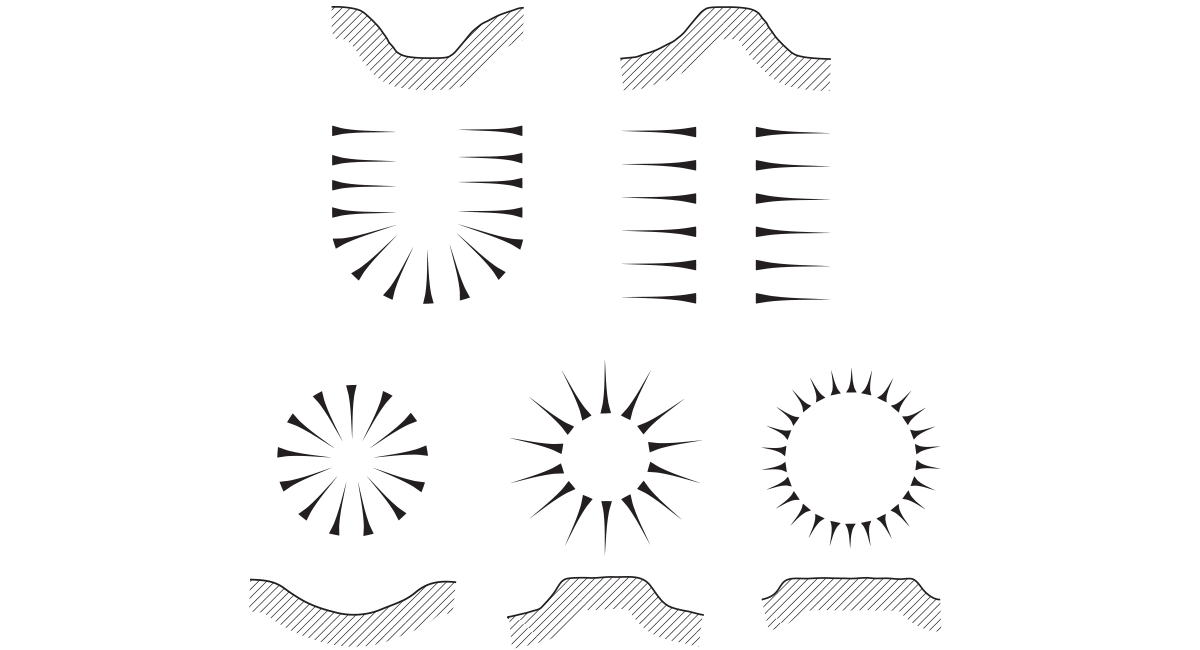

Map makers and archaeologists show small bumps and dips in the ground using marks called hachures.

The triangular shape indicates the direction of the slope – the narrow end always faces downhill. Image: ‘Hidden Histories by Mary-Ann Ochota / Frances Lincoln 2016’

You’ll see these on OS maps to show earthworks and mounds, for example.

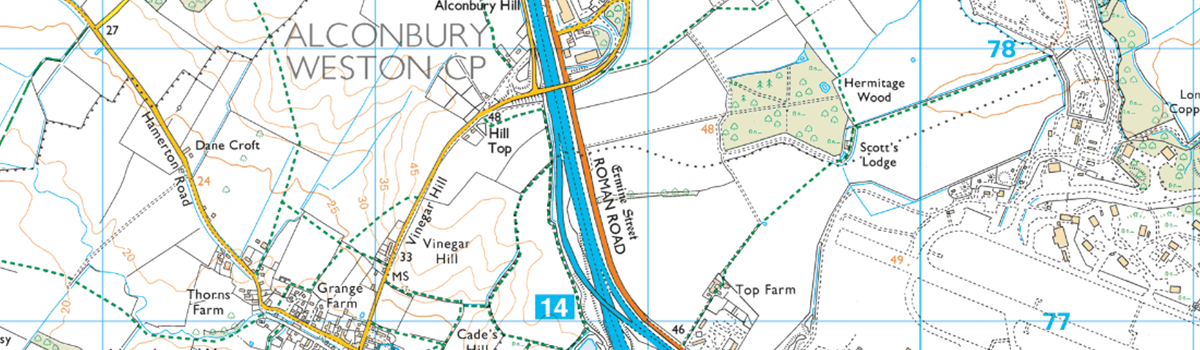

Roman roads on a map

If a stretch of road or an earthwork has been confirmed as being originally Roman, it’ll be marked in capitals, in a sans serif font. Sometimes you’ll see one section of Roman road marked, but then the modern road curves away elsewhere. Look on the map to see if you can trace the original route of the Roman road – it’s sometimes preserved in field boundaries, minor roads, footpaths or parish boundaries. You may be able to trace it to another section of marked ROMAN ROAD.

The Great North Road (now more commonly known as the A1 and in parts the A1 (M)) from London to Scotland is a great example of modern roads and Roman roads meeting on the map.

At least 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of Roman road were built in Britain, mostly before AD150, and they used the existing network of earth tracks and routes that the Iron Age Britons used. It’s a myth that Roman roads were dead straight, regardless of the terrain – they were more pragmatic than that.

Roman roads are straight – but in sections. Look out for clues on your map that might show where Roman surveyors decided to change direction in order to reduce the gradient up hills, or to avoid obstacles.

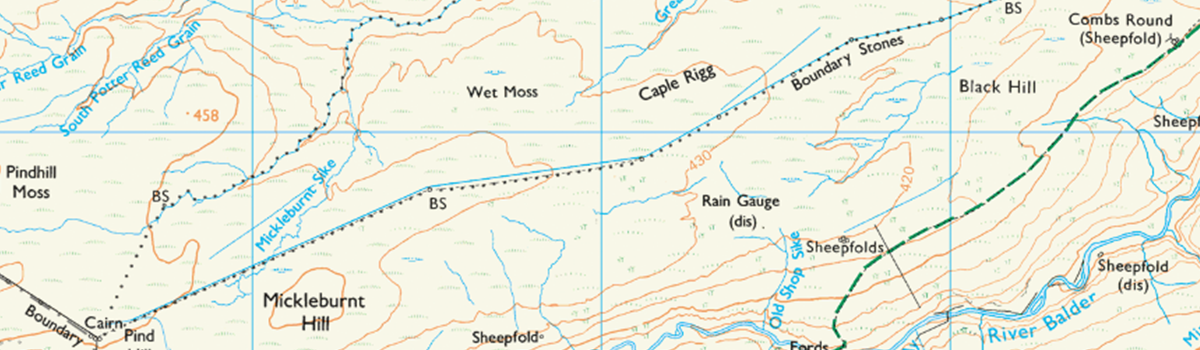

Boundary markers on a map

Look closely and you’ll often see MP, MS and BS marked on your map, next to a faint dot. MP is a milepost, MS is a milestone, BS is a boundary stone. These are quite fun targets if you want to practise your navigation skills – and when you do reach the stone, it will usually have interesting markings on it.

Milestones

The Romans were the first to standardise distances between road markers. They’d erect a cylindrical standing stone at every Roman mile (1480m, which was officially 1,000 double paces), marked with the distance to the next important site, and the name of the Emperor whose reign it was. A few of these still survive – check the online heritage registers kept by Historic England, Historic Scotland and CADW for the locations of Roman milestones.

Most milestones you’ll see date from the 1700s or later, when new Turnpike roads were legally required to have milestone markers. It meant passengers and goods carried on the stagecoaches could be charged standardised rates for the distance they travelled. You’ll also see plenty of milestones along canals, also used to calculate how much people would be charged for moving their goods by barge.

Boundary stones

These usually still mark modern parish boundaries – look to see if there are grey dashed lines on the map that run up to and away from the stone. On the stone itself, look for initials that indicate which parish boundaries are marked by the stone. Usually it’s just two, but sometimes a stone marks the intersection of three parishes.

Boundary Stones near Brough in The Pennines

Throughout the medieval period and into the 1700s, the right to collect peat for fuel from moorlands or ‘mosses’ was carefully protected. Each township or manor was allocated a section of the peat beds and in some places, engraved turbary stones were used to mark the boundaries of different peat beds. Surviving turbary stones are rare, but they can also have initials carved into them to show which township claimed which part of the moor.

Map-makers marks to spot in the landscape:

Bench Marks

When you’re on an outside adventure you may see a symbol of an engraved upward arrow pointing to a horizontal line on buildings and fixed features like milestones. These are Ordnance Survey Bench Marks (BMs). They were established to accurately map land heights above sea level. The network is no longer maintained, as GPS and high-accuracy points are used for heighting the land instead. There are around half a million defunct BMs around the country.

Bench Mark found on a church

A Flush Bracket on a Trig Pillar.

Flush Brackets are metal plates fixed to walls that provided additional OS BMs. They’ll have the arrow pointing to a horizontal line, as well as a series number. Trig Point pillars (often found at the top of hills) have Flush Brackets at their base.

Although not quite as old, many people consider these to be archaeological features of the future!

Now it’s your turn to GetOutside and unearth some hidden history for yourself.

Entertaining and factually rigorous, Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape by British broadcaster and anthropologist, Mary-Ann Ochota, will help you decipher the story of our landscape through the features you can see around you.

Banner image: MaryAnnOchota.com Credit: Simon Fox